The rippling effects of war last long after the heartbreak of battle. The pre D-day sinking of HMCS Athabaskan in the English Channel is a personal case in point. My grandfather, Leslie Ward, was one of 128 Canadian sailors to perish with his ship in the early hours of April 29, 1944. I first learned of that loss as a young boy from my father, Peter. Decades later. I would dive 285 feet to his father’s submerged gravesite to honor a crew’s sacrifice and seek answers to the mysterious sinking of HIMCS Athabaskan.

“I thought about my grandfather losing his life amid the chaos and fear of that night along with 127 other young men.”

“I thought about my father sitting in a boat almost three hundred feet above and realized how anxious he might have been, waiting to see if the same waters that claimed his father would be kinder to his son.”

Athabaskan’s life began with an unlucky berth. While she and her sister ship. HMCS Iroquois lay under construction at Newcastle On Tyne. Iroquois was badly damaged by German bombers and because she was preordained to become Canada’s first Tribal Class Destroyer, bureaucrats chose to switch nameplates with Athabaskan rather than delay her important launch.

That decision seemed to haunt Athabaskan through her brief life. In just over a year of service she suffered damage from bad weather and accidents, was nearly destroyed by one of Germany’s first glider bombers and ultimately ripped apart 5 mils off the coast of France. No wonder she was dubbed “Unlucky Lady.”

Despite these indignities, Athabaskan performed admirably as one of only four Canadian Tribal Class Destroyers and she remains the most important warship to be sunk in Canadian naval history. Yet for all her wartime import, public awareness of Athabaskan’s sinking faded over the years. In the early 1980s, the publication of “Unlucky Lady, The Life and Death of HMCS Athabaskan” by Emile Beaudoin and Len Burrow helped reawaken an interest in the subject. As a new diver the book fueled my wonder about possibly visiting her wreck site one day.

That possibility became more real in 2000 when I met Canadian filmmaker Wayne Abbott who was working on a documentary about Athabaskan and her survivors. Our mutual passion for the subject led to plans for finding the wreck and mounting a dive expedition focused on honoring her crew and solving the mystery of her untimely death. To unravel the mystery meant going back in time to Athabaskan’s last living moments.

Throughout the spring of 1944 allied naval forces carried out anti-shipping sweeps to erode German naval strength in preparation for the invasion of northwest Europe. As part of the effort, Athabaskan and her sister ship HMCS Haida were ordered to act as distant covering force for eight Motor Launches (MLs) of the 10th ML Flotilla. The launches were to lay mines about nine miles north of the eastern point of the Ile de Bas, an island off the northwest coast of France.

As the Tribals headed out in the early morning hours of April 29, 1944, the coastal radar station at Plymouth Command detected two enemy vessels off the French coast. At 0307, the C-in-C Plymouth, Admiral Sir Ralph Leatham, ordered Haida and Athabaskan to proceed southwest at full speed to intercept.

At 0359 Athabaskan picked-up targets on radar, later confirmed as German destroyers T-24 and T-27. Haida concurred and an enemy report was made. The Tribals embarked on an intercept course and at 0412 the order was given to engage the enemy. The battle had begun. At 0417 Athabaskan was rocked by an explosion on her port side, aft. Crippled and badly on fire the crew struggled to keep their ship afloat. At 0427 a massive explosion broke her apart and with bow raised, she sank in minutes.

The cause of that first explosion likely came from a torpedo fired by the German destroyer T-24 as it turned away eastward. The cause of the second explosion that sent Athabaskan to the bottom became the subject of great controversy. Some survivors still claim she was the victim of friendly fire – a tragically mistaken attack by a British Motorized Torpedo Boat (MTB) launched in the confusion of battle.

According to official investigations shortly after the sinking and subsequent examination by historians, the large fire that burned out of control after the first explosion led to a chain of events that caused the second, and by virtually all accounts, more powerful internal explosion. The only way to solve the mystery would be to visit Athabaskan and see if the ship would give up her secrets. But first we had to find her.

Our search was aided by Jacques Ouchakoff, president of the French Athabaskan Associations Armed with only a depth finder and small ROV, Jacques had searched the waters off France’s Brittany coast for years with no sign of Athabaskan. Then, in the fall of 2002 he located a promising subject in 285 feet of water about 5.5 miles off the coast off Brittany. Images from his ROV revealed two large guns and an ammunitions locker – clear evidence of a warship. It was enough encouragement to proceed with planning for the dive expedition and documentary effort. For me, the excitement of locating a likely target was tempered the realization that diving to the ship at 285′ would require intense training and specialized equipment. I had accumulated hundreds of dives over almost 20 years but nothing close to this depth or in these conditions. I would need to learn fast too because our window for the expedition was just one week, toward the end of July.

I asked Orlando-based deep dive instructor and Cambrian Foundation president, Terrence Tysall for his help and he generously agreed to train me and participate in the expedition. Coincidentally, my role as public affairs coordinator for NOAA’s Aquarius Undersea Lab offered me the opportunity to train as an aquanaut and saturate in Aquarius during an April training mission. Aquanaut dive training closely parallels that of deep, or “tech” diving, which gave me a good start.

Terrence likened the goal of training me for the 285-foot dive to that of transforming an Appalachian Trail hiker into a Mount Everest climber. The course overview was daunting and the equipment needs extensive. Equipping yourself costs twice as much because redundancy is the golden rule in deep diving. After all, you can’t simply pop up to the surface from a couple hundred feet to replace a broken light or snapped fin strap. Product value takes on a whole new meaning when your life is on the line.

I thought I would really enjoy the month of training dives off Boynton Beach, FL but it was “boot camp” intense. Late night study sessions, dive-planning and gear-prepping, then pre-dawn sorties, pitching seas, hamperingly heavy equipment and that sinking feeling one gets upon realizing there is no turning back – in my case before dropping off the stern for yet an-other deeper dive. It reminded me of my only parachute jump – only here the call to action was, “Dive! Dive! Dive!”

The whole experience gave me a sense for the fear and apprehension that surely grips anyone approaching battle. I found myself imagining how my grandfather must have felt setting out from Plymouth on his first and last battle. It also added meaning to Terrence’s training mantra, “better to sweat in peace than bleed in war”.

That phrase was cold comfort in the face of numerous tests. It seemed Terrence had arranged for unseasonably cool conditions to mimic the English Channel. Without a hood, the 48 degrees water turned into migraine making vice grips. The cold, dark conditions mixed with the deep air diving to produce mind-numbing nitrogen narcosis, accented by a frightening broken mask strap on one dive to 180′.

There were several unwelcome marine life encounters too. In one narced-out state I was “bonged” at close range by a 500lb Goliath grouper. During deco stops I was harassed by a stubbornly affectionate remora, and circled by a hammerhead shark (the urge to emerge was chilled by the fear of getting bends). In all we packed in 15 training dives over one month, each one deeper than the previous, ending with a dive to 305 feet. Two days later we left for France.

In addition to preparing myself for the coming dives I had been serving as the expedition coordinator, planning our objectives and sharing information with the many people who would participate in the project. That meant brushing up on my French, as many of the participants were native “Bretagnes.”

Finally, after years of imagining and months of planning, 25 people converged near the tiny town of Plouguerneau in Brittany, France on July 19. Our headquarters for the expedition was an old country home near the coast, 5.5 miles due south of Athabaskan’s resting place. We quickly converted the charming old house for our purposes, prepping camera equipment and tacking up massive blueprints for frequent briefing sessions.

The participants included two French boat captains (including the discoverer of the wreck site) and their crew. The production crew numbered just four, including Wayne and his wife Jocelyne. We were honoured to be joined by two Athabaskan survivors, Wilf Henrickson and Herm Sulkers. Two representatives of the Canadian Navy were on hand to help analyze footage from our dives and about a dozen other Canadians made the trek including relatives of Athabaskan. My father was there too, visiting, for the first time, the area where his father had perished.

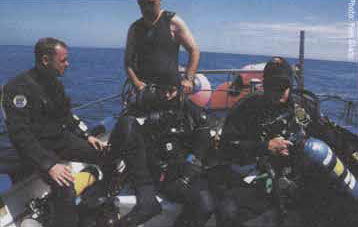

The multinational dive team consisted of local divers Franck Leven and Yves Gladu, Andy Pitkin, an English doctor formerly with the Royal Navy’s hyperbaric department, Terrence from the USA and myself, representing Canada.

Our window for diving stretched five days from Monday, July 21 to Friday, July 25. The tides in that region of the English Channel can whip up currents exceeding 5 knots so our dives were timed to occur precisely at slack tide, when tidal flow stops to reverse direction. We lost 2 days to bad weather but accomplished a lot in 3 days.

It had been almost 9 months since the wreck had been discovered and still no one had ever dived on Athabaskan. So, on dive day one we had to first relocate the ship and secure a downline. The exercise took almost two hours, bringing us dangerously close to the point of missing slack tide, but four divers did go down, returning with valuable footage from three video cameras. I stayed onboard the ROV ship with the camera crew who had hoped to video my reaction to seeing live footage from the wreck, but the ROV missed its mark and unfortunately failed to operate properly throughout the week.

Tuesday, July 22, was a beautiful day to dive. The winds had calmed the seas to about 5-foot swells and the clear skies allowed the sun to warm air temps to near 80. I went down with Terrence and Andy to deploy a 30-pound brass plaque presented to us by the Canadian Navy as a permanent memorial to all Athabaskans. Herm Sulkers had also given us the POW dog tag he had worn for the last year of the war. He wanted us to leave it with his ship and fallen crewmates.

The Descent seemed to take forever as the green water gave way to darkness. It seemed like I was going back in time with each pull on the line until finally we hit the bottom at 285 feet and the events of April 29, 1944 seemed to come alive. The debris strewn across the sea-floor seemed to echo the chaos of battle. Nothing of the ship looked intact. The onslaught of daily tidal currents had ripped her open, and spread her remains amid the rocky and silty bottom. Despite the shock of seeing the once proud ship all beat-up, I felt a warmth at our meeting. The rhythmic resonance of my breathing apparatus produced an eerie yet serene sound, softened even more by the slight narcotic effect of my bottom mix breathing gas (50 He/ 16 02/34 N2). I approached the slightly inverted hull and kneeled next to the ship’s bilge keel, which had rolled upward (indicating a slight “turtling” of the ship). As Terrence cut the Navy plaque from its harness I began to reflect on the incredible place.

I thought about my grandfather losing his life amid the chaos and fear of that night along with 127 other young men. I thought about my father sitting in a boat almost three hundred feet above and realized how anxious he might have been, waiting to see if the same waters that claimed his father would be kinder to his son.

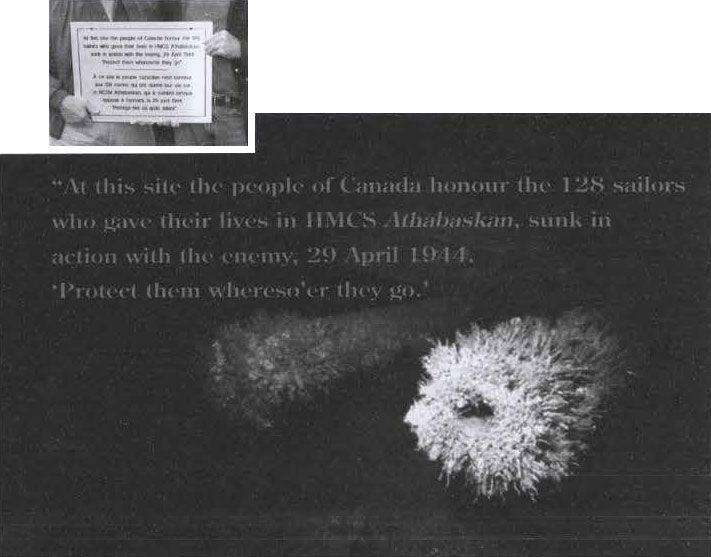

I grasped the 30lb brass plaque it in both hands and still kneeling, as if in church, placed it lovingly against her bilge keel and read the inscription: “At this site the people of Canada honour the 128 sailors who gave their lives in HMCS Athabaskan, sunk in action with the enemy, 29 April 1944. Protect them whereso’er they go.’

I thought about the painful sacrifices demanded by war, the suffering it exacts and the impact on so many lives over so many years. And I thought about my own journey to this distant, solemn spot, the challenges of getting there and the many reasons for returning safely. Mostly I was calmed by the reverence of the occasion – a peace reflected in my ample remaining gas supply.

At fifteen minutes of bottom time, our tables dictated it was time to ascend and Terrence was happy to put my training to the test. I retrieved my lift bag and cave diving reel and prepared to deploy the bag as I had imagined I would a dozen times before. I unfurled and inflated it sending it on a near 300 ft journey to the surface.

We trailed behind it at the prescribed rate stopping first at 140′ then increments of 10′ for varying minutes. The hour-long de-compression was uneventful but bitterly cold. Even in my new dry-suit, I could appreciate the suffering of the survivors who floated for four hours before being plucked from the sea by the Germans.

I counted the seconds down as the time for our final 100% O2 decompression stop ended and we ascended. Breaking through into sunlight, I was met by the producer and cameraman in a Zodiac. I returned the distant salute of the two survivors Herm and Wilf and warmed to the realization of an incredible adventure. I degeared and swam to the dive boat, where my father helped me aboard and got a big salty hug. We finished the week with just one more day of diving but gathered almost two hours of underwater video footage.

“The sacrifice of those lost in war has an enduring power to inspire respect and fascination long after the loss.”

“That power drove me to reach deeper than I thought possible to meet the grandfather I never knew and honour his ship and crew.”

Over the ensuing months that footage was reviewed, argued over and dissected. The compelling conclusion: the ship’s death was caused by internal explosion not friendly fire from by a British MTB torpedo. Wayne edited over 30 hours of raw footage into an hour-long documentary for History Television Canada. “The Mysterious Sinking of HMCS Athabaskan” aired nationally on April 29, 2004: sixty years to the day after that Unlucky Lady went down. The effects of that tragedy continue to touch people today.

Read more at divermag.com October 2004