Ontario’s waterways have long been recognized for their roles as the lifeblood of transportation and a centre of recreation. That’s just on the surface. A deeper appreciation is growing for what lies underwater, as recreational scuba divers and marine enthusiasts discover Ontario’s sunken treasures.

No longer the exotic preserve of a daring few, scuba diving is becoming as popular and as accessible as alpine skiing. It’s a sport that is opening up a whole new frontier to the average adventurer. If you do not have a breathing or lung problem and you can swim, you can dive. As more and more people explore the depths on scuba, important clues to Ontario’s history are being discovered within her rivers and lakes.

Thousands of shipwrecks have been found in Ontario waters, each revealing a precious clue to our maritime history. No other region in the world can boast so many freshwater-preserved artifacts; not surprising, since Ontario grew up on the Great Lakes, depending on transit-by-water for everything from food and commerce to mobility and communication.

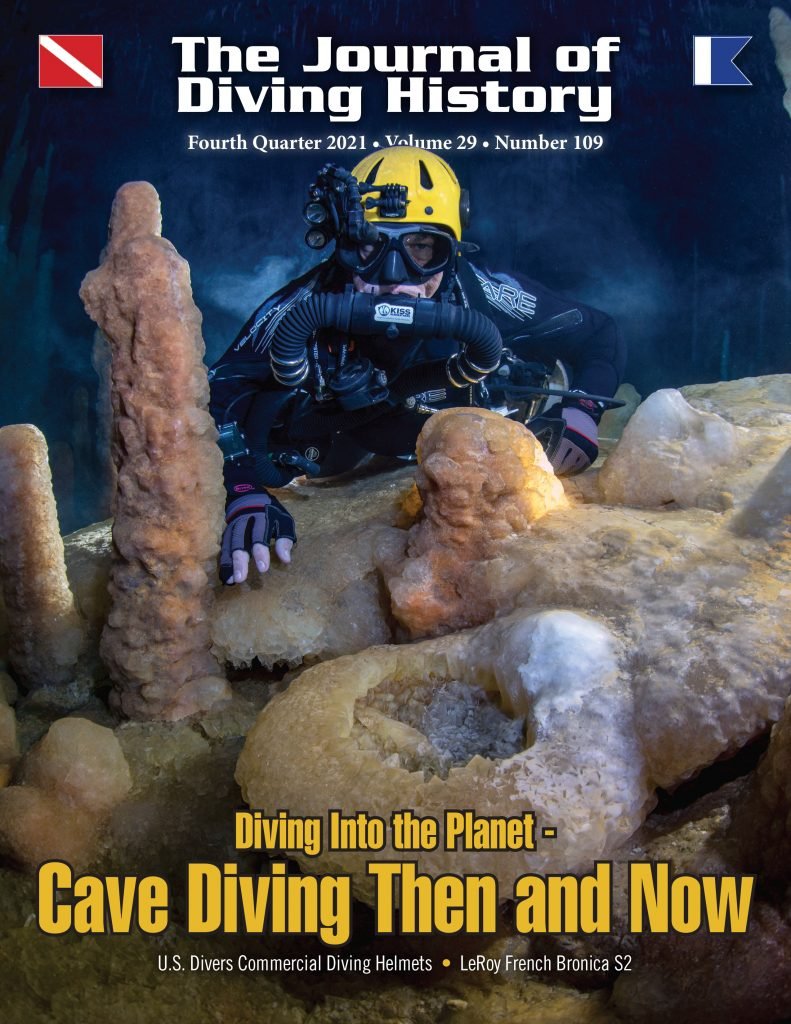

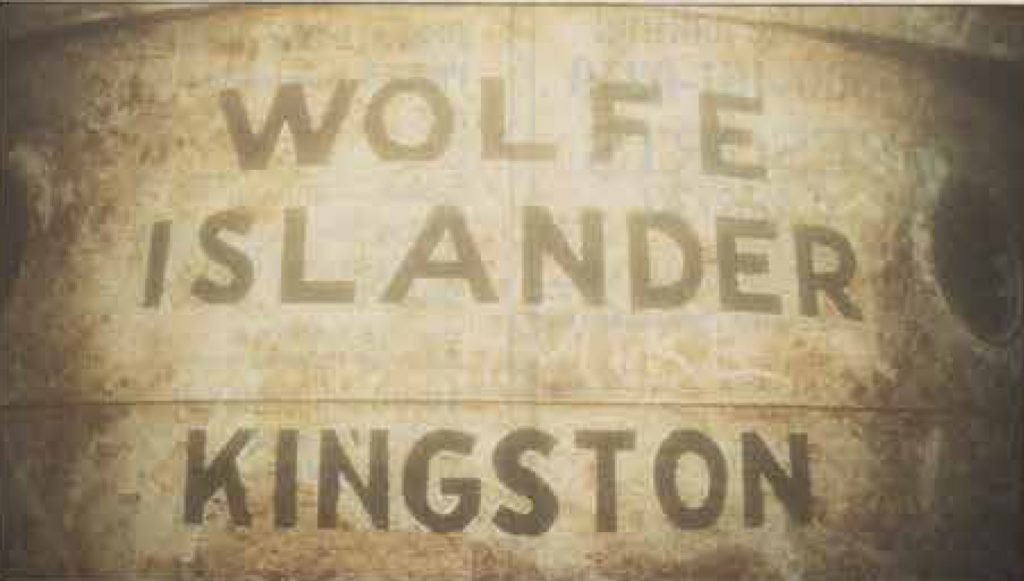

The excitement and enjoyment of wreck diving has even led to the deliberate sinking of vessels, as in the case of the M.V. Wolfe Islander. The 165-foot steel ferry linked Kingston to Wolfe Island from 1935 until 1957. Retired and unwanted, she was acquired in 1985 by Kingston divers who prepared her for a permanent resting place 80 feet beneath the surface. She now acts as a scuba divers playground attracting thousands of underwater visitors each year.

Few ships are as carefully placed and easy to find as the Wolfe Islander. Most shipwrecks are discovered either by fluke or after months, even years, of in-depth research and tedious underwater explorations. The discovery of the Hamilton and Scourge in 1973, for example, was a result of painstaking archival study and exhaustive dives through the waters of Lake Ontario.

The two American armed merchant schooners were lost in a sudden squall near Hamilton during the war of 1812. After determining the probable location of the vessels, a search team went out and combed the lake bottom with side-scan sonar until the vessels were found under 230 feet of water. Both ships are sitting upright, almost perfectly preserved in the cold depths of Lake Ontario. Remote photographic surveys have given archaeologists a clearer picture of the era’s ship building techniques and have revealed valuable facts about the ill-prepared American navy in its war with Britain.

Although the depth of some wrecks, like the Hamilton and the Scourge, puts them out of the range of sport divers, a great many more lie in easy-to-reach waters. The greatest concentration of accessible shipwrecks in Ontario can be found off the tip of the Bruce Peninsula, where Lake Huron meets Georgian Bay. Here, within the crystal-green waters of Fathom Five Underwater Park, Canada’s first underwater park, lie at least 21 known shipwrecks.

The focal point for the park is Tobermory, a small port that thrived as a haven for weather-weary ships and now hosts thousands of eager tourists each year. The town revolves around its maritime life as divers, boaters and sightseers cruise in and out of the harbour to explore the region’s attractions.

For divers, it’s a dream come true: clean water, good visibility and so many wrecks it would take weeks to explore them all. Fathom Five is considered to possess the greatest collection of freshwater wrecks on the continent, if not the entire world.

Complementing the fleet of sunken ships are beautiful and unusual geological formations. Ancient glacial retreats and water erosion have sculpted the limestone foundation, creating enormous, pockmarked rocks and mysterious subterranean caves. The impact of geological events that transpired millions of years ago can still be seen and felt today.

On land, remnants of the province’s prehistoric past are no less dramatic. Towering columns of earth and rock, like maritime hoodoos, were chiselled out of the bluffs of one island named Flowerpot because of the flower-topped rock towers that dot her shores.

With so much to enjoy in and around the water, Tobermory satisfies both divers and non-divers, For marine enthusiasts not inclined to take the plunge, the wonders of the underwater world can still be experienced through glass-bottom boats. As the crafts cruise across the surface, spectators peer down onto shallow wrecks and beautiful rock formations.

One of the most popular destinations for glass-bottom boaters and divers alike is a pair of old wrecks resting in 20 feet of water. The schodner Sweepstakes and the steamer City of Grand Rapids are easily reached by boat near the end of Big Tub, a large harbor just west of Tobermory. Of the two, the Sweepstakes seems to best symbolize Ontario’s marine heritage.

She was launched in the year of Confederation from Wellington Square (now Burlington), then a

major center of maritime commerce. For nearly 20 years, she hauled ‘cargo throughout the province during the golden years of sail. Then, ironically, in 1885, the year our national railroad was completed, foreboding the sunset of the heyday of sail, the Sweepstakes became stranded off Cove Island, and was ultimately towed into harbor where she sank.

As more people venture down, more sites are discovered and. This encourages more diving. This growing trend has spawned brand-new tourist destinations and generated millions of dollars in diving spinoffs.

Unfortunately, the influx of recreational divers has placed a strain on underwater artifacts. Pirates, souvenir seekers and salvage operators have stripped some ships to the bone, defrocking them of the historical clues they offer.

To conserve Ontario’s marine heritage, a number of groups have taken up the challenge of sensitizing diving public to the importance of Bae shipwrecks.

One of the largest organizations in this conservation crusade is Save Ontario Shipwrecks (SOS), a non-profit organization made up of sport divers and amateur marine archeologists. Established in 1981, with the support of the Ontario Government, SOS has become an unofficial curator of the province’s underwater “museums.”

In addition to their role as educators, local SOS chapters chart sunken resources, survey shipwrecks and piece together our maritime history through archival study and pictorial collections. These activities are encouraged and supported by the marine Heritage Unit of the Ministry of Culture and communications. The Ministry also provides funding, expertise and on-site support.

The arrangement is unique in North America and has earned Ontario divers respect and admiration

from the world’s diving community. Best of all, the cooperative work has made dozens of shipwrecks more interesting to-explore by sharing the stories each site has to tell.

The variety of subjects isn’t restricted by type, location or age either. They range from an inundated the mining town up the Ottawa Valley to sunken ships, locomotives and aircraft in lakes, rivers, and quarries around the province. Divers have discovered pots near Gananoque dating back to.300 B.C., while recent additions to the depths, like the 1975 sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald in Lake Superior, become almost instant legends.

The shipwreck Lillie Parsons is a good example of how Ontario’s history is being discovered and preserved by groups like SOS, launched on September 14,1868, the wooden a schooner was a conduit of commerce between Great Lakes ports from Brockville to Chicago. Her life span was abruptly cut short in August of 1877 as she headed for Brockville with a load of coal. It was a calm Sunday and the Lillie’s email crew would have been flying all her sails to increase steerageway through the treacherous narrows of the St. Lawrence River.

The calm was suddenly over-whelmed by a tremendous squall. Pushed over, her cargo of coal thrown to one side, the Lillie began to list and take on water over the railings. Her startled crew would have scrambled frantically to pull down sails, but to no avail. There was no saving her. The crew made it, but the Lillie went down on the shoal of a nearby island.

Years later, time and the relentless currents conspired to pull her under where she now lies, upside down and parallel to the current. She slopes down with her stern in 40 feet of water and her bow at about 50 feet. To dive on her, a short boat trip to Sparrow Island is necessary. Her original anchor was retrieved and erected on the island with the chain leading back to the ship. This inverted anchorage now acts as a unique point of departure for scuba divers.

Slipping beneath the surface from shore, you work your way down the chain, like a repelling mountain climber in slow motion, only here the current, not gravity, is the main force. Before long, the stern of the Lillie is visible, you let go of the chain and propel yourself downward following the Hull to the depths.

Something glistens on the side of the ship. You move in for a closer look. A bronze information plaque has been fastened to the hull; part of the work done by SOS divers. Her along you notice another plaque which explains the peculiar aluminum trough jutting out from the hull. It’s full of artifacts that went down with the Lillie Parsons.

Many articles were retrieved, recorded and carefully returned to the Lillie for the enjoyment of all divers.

SOS plans to upgrade the presentation by replacing the trough with a sealed, plexiglass display case full of authentic artifacts preserved in solution. Many other wrecks can expect similarly conscientious treatment as SOS continues its museums-of-the-deep initiatives.

Local SOS chapters have prepared profiles on dozens of shipwrecks, outlining their histories, explaining their present condition, and offering interpretive trails complete with well-marked access points and identification plaques. Just east of the Lillie Parsons ‘resting place, two more SOS finds have been charted near Prescott: the Conestoga and the Rothesay.

The Conestoga, a finely crafted wooden steamer, was launched in 1678, a time when steamers were replacing sailing ships as the workhorses of the Great Lakes. The quality of workmanship was heralded at the time of her launch by a Cleveland paper “. . . fitted out in all proportions with a care to strength, durability and beauty. It’s estimated that her cost will be near $90,000.”

But by 1922, when she met her disastrous end, she had become as inefficient as the sailing ships she was built to replace. After 44 years of hauling cargo, she mysteriously caught fire at lock 28 of the Old Galop Canal near Prescott. All her crew had left the ship, leaving no belongings aboard. Despite efforts to quell the flames. little could be done to save her. She was flushed out of the locks, drifted downstream, ran aground and finally sank in about 30 feet of water.

Her black, rusted smokestack is rote from shore, rising 10 feet above the surface. Beneath the waves the Conestoga’s 200-foot shell offers divers a chilling exhibit of a 19th-century steamer’s remains.

The Rothesay was built in Saint John, New Brunswick, in 1867 and is one of only a few ocean -launched vessels to ply Ontario’s waterways. Her great size and construction as a wooden side-wheeler made her a major attraction for the passengers she ferried between Montreal and Brockville until 1903.

At the time she was the largest excursion ship on the St. Lawrence, measuring 193 feet by 29 feet. In 1903 she collided with the tugboat Myra about a mile upstream from Prescott. All the Rothesay’s 60 passengers made it safely to shore in lifeboats. Two of Myra’s crew were lost in the tragedy.

The Rothesay lies in two sections about 300 yards offshore in 30 feet of water. Her two paddle wheels are visible, as are the remains of her boilers and engine. To reach her, divers swim out from shore to a buoy, and descend to a series of guidelines that lead all the way to her hull. The visibility is about 15 feet, which is above average for the St. Lawrence.

Throughout the province, underwater monuments rest silently, waiting to tell their stories to those who venture to see them. Although each visitor may approach the experience differently — on scuba or snorkeling or gazing through the hull of a glass bottom boat — every visit unconsciously pays tribute to a romantic era of Ontario’s past.